Dieser Podcast von Arcoplexus befasst sich mit der Autorin Ines Sachs und ihrem Buch „Apéro um zwölf“, das ihren Umzug von Deutschland nach Südfrankreich humorvoll dokumentiert. Das Buch dient als praxisorientierter Ratgeber für Auswanderer und beleuchtet Themen wie administrative Hürden, die Bedeutung der Sprachintegration sowie soziale Rituale wie den französischen Apéro. Ergänzend dazu bieten die Texte Einblicke in Sachs’ beruflich geprägten Hintergrund als Projektmanagerin und ihre verschiedenen digitalen Kanäle zur Unterstützung von Frankophilen.

Category: Côte d’Azur

-

Buchbesprechung “Deutsche Exilanten”

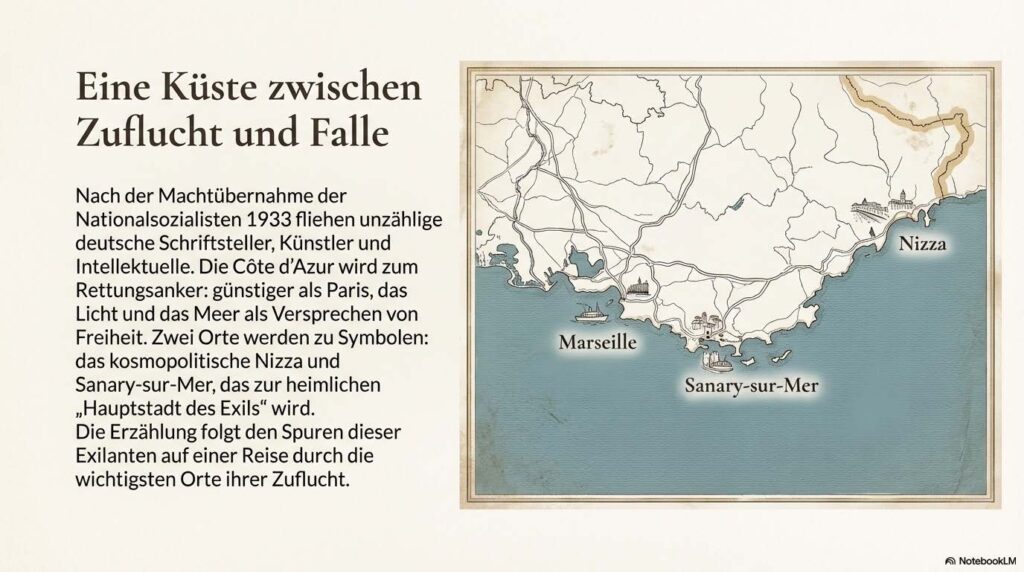

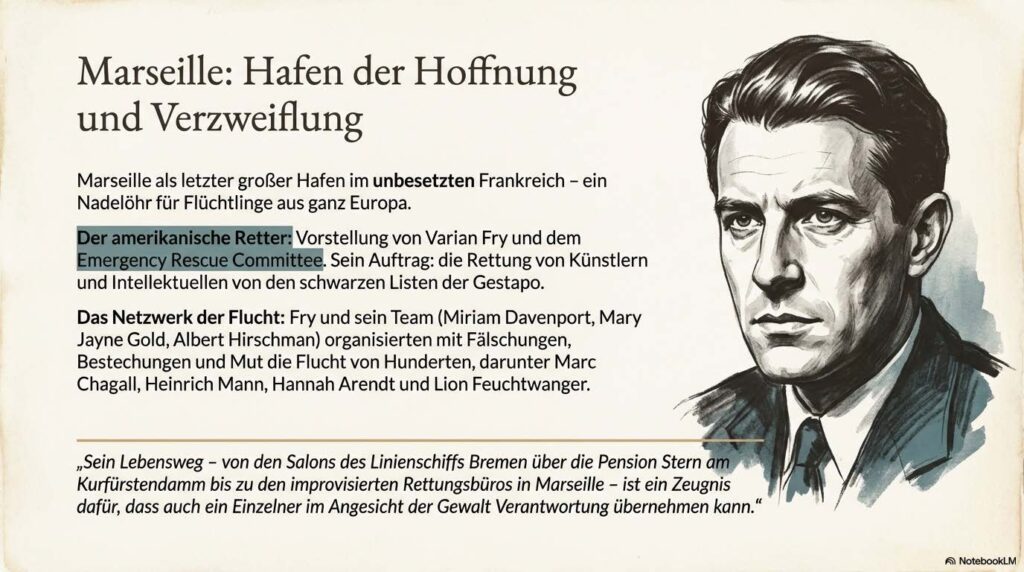

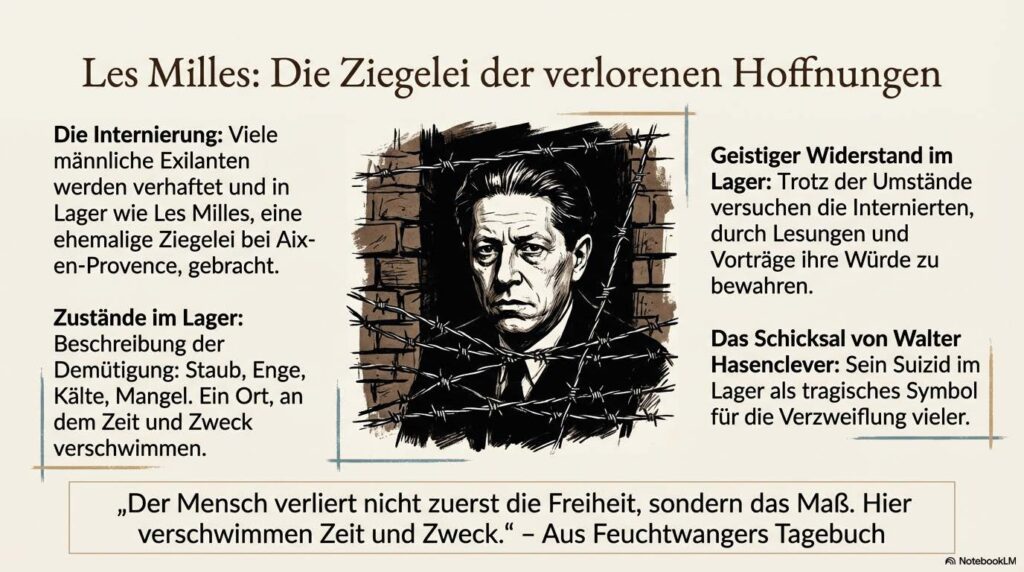

Podcast von Arcoplexus zum Buch “Deutsche Exilanten an der Côte d’Azur” von Klaus Kampe. Das Werk dokumentiert das bewegte Leben deutscher Exilanten an der Côte d’Azur während der 1930er Jahre. Im Fokus stehen Zufluchtsorte wie Sanary-sur-Mer und Nizza, wo bedeutende Intellektuelle wie Thomas Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger und Hannah Arendt versuchten, ihre kulturelle Identität gegen das NS-Regime zu verteidigen. Die Texte beleuchten zudem die mutigen Rettungsaktionen von Varian Fry in Marseille sowie die künstlerische Arbeit des Fotografen Walter Bondy. Neben literarischen Analysen und historischen Fakten fließen persönliche Anekdoten und fiktive Dialoge ein, die das Spannungsfeld zwischen mediterraner Idylle und existenzieller Bedrohung spürbar machen. Letztlich dient das Buch als Hommage an die schöpferische Kraft einer Generation, die trotz Verfolgung und Internierung an Humanismus und Freiheit festhielt. Es verbindet dabei die historische Spurensuche mit dem kollektiven Gedächtnis einer verlorenen Welt. Zum Buch:

-

The Pink Villa of Cap Ferrat – A jewel on the Côte d’Azur

On the prestigious French Riviera, on the Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat peninsula, stands one of the most famous villa estates on the Côte d’Azur: the pink villa, now called La Fleur du Cap. This property is a fascinating example of late 19th-century luxury architecture, which over time has been home to a remarkable series of prominent residents and has become a setting for the social and cultural history of the Riviera.

Architecture and construction history

The villa was built in 1880 by Albert Bounin, the son of a Sardinian arms dealer and olive oil merchant from Nice. Bounin acquired several plots of land on the quiet headland of Cap Ferrat and had a picturesque estate built there, which he initially called L’Isoletta and which had a small private harbor. From the outset, the building captivated visitors with its location directly on the sea and its striking pink façade, which would later give it its name.

Later, his son Paul took over the estate, added an extra floor, and renamed the villa Lo Scoglietto (“the little rock”). During these early years, the house remained largely hidden from public view, but it soon became a notable destination for wealthy travelers on the Riviera.

Prominent residents in front of Niven

During the first decades of the 20th century, the villa changed owners and tenants several times:

- In 1920, the Duchess of Marlborough, Consuelo Vanderbilt, one of the most prominent society figures of her time, lived there for a while.

- In the 1950s, the villa was occupied by King Leopold III of Belgium shortly before his abdication.

- The silent film and early sound film star Charlie Chaplin spent several weeks at the estate.

This series of famous guests shows how strongly the Riviera had become a refuge for aristocrats, movie stars, and wealthy travelers since the early 20th century—a trend that also had a strong influence on the image of the villa.

David Niven and the Riviera Era

Perhaps the most famous resident of the pink villa was British actor David Niven (1910–1983). Niven bought the villa in the late 1950s/early 1960s and made it his long-term home.

David Niven was one of the most charming and versatile actors of his generation. A Hollywood star, author, and former officer, he was considered an elegant gentleman with British charm. Niven was closely connected to the international celebrity scene on the Riviera: he was friends with Princess Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier of Monaco and was one of the well-known personalities who shaped the lifestyle of the Côte d’Azur in those years.

During this time, the pink villa was not only a private residence, but also a place for social gatherings. Niven also played a cinematic role as part of the estate: a scene from his film “Trail of the Pink Panther” (1982) was shot here — an ironic reference to the villa with its striking color and celebrity connections.

After his death in 1983, the small square in front of the villa was named Place David Niven — a lasting testament to the actor’s influence on local culture and the collective memory of Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat.

NAfterlife and restoration

Over the following decades, the property changed hands several times; since 1999, it has belonged to the parents of New Zealand billionaires Christopher and Richard Chandler, who had it extensively restored. Today, the villa is called La Fleur du Cap and is larger and better maintained than ever before — a monument to the glamorous era of the Riviera.

Conclusion

The pink villa in Cap Ferrat uniquely embodies the history of the Côte d’Azur: it is an expression of luxurious 19th-century architecture, a reflection of an aristocratic and cinematic society, and at the same time a place where the lives of prominent personalities such as David Niven have materialized. Its bright color and spectacular location above the sea make it a symbol of glamour, elegance, and the cultural appeal of the French Riviera to this day.

-

Berliner Tageblatt, “Ten Years of Nice”

Kurt and Theodor Wolff, the Berliner Tageblatt, “Ten Years of Nice,” and Alfred Neumann—Facets of a Liberal Public Sphere.

These men were primarily active in the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, with a focus on the period between the German Empire and the Weimar Republic. The history of the German press and intellectual world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is hardly conceivable without the Berliner Tageblatt. As one of the most important liberal mass-circulation newspapers of the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, it was not only a news medium but also a forum for political debate, literary innovation, and European self-understanding. This environment attracted personalities such as Kurt and Theodor Wolff and authors such as Alfred Neumann, whose contributions exemplify the connection between journalism, literature, and political thought.

Theodor Wolff, long-time editor-in-chief of the Berliner Tageblatt, had a decisive influence on the newspaper. He understood journalism as a moral and political task. Under his leadership, the newspaper developed into a voice for liberalism, the rule of law, and understanding between European nations. Wolff’s editorials combined analytical acuity with linguistic elegance and made the Berliner Tageblatt a leading medium for the educated public. His work showed that political journalism could be more than mere reporting: it became intellectual intervention.

Kurt Wolff, although not directly part of the editorial team, represented a similar intellectual attitude. As one of the most important publishers of the 20th century, he promoted authors of literary modernism such as Franz Kafka, Georg Trakl, and Else Lasker-Schüler. The proximity between the press and literature, as evidenced in the environment of the Berliner Tageblatt, points to a common cultural project: the renewal of language, thought, and social sensitivity. Kurt Wolff’s publishing work thus complemented Theodor Wolff’s journalistic work on a different, literary level.

One example of the Berliner Tageblatt’s European perspective is its review “Ten Years of Nice.” Such articles were typical of the paper: they combined current politics with historical reflection. The reference to Nice—as a venue for international conferences and diplomatic negotiations—symbolizes the paper’s interest in European power relations, peace agreements, and Germany’s role in international politics. Reviews of this kind served not only to inform readers, but also to educate them politically.

Alfred Neumann, who contributed to the intellectual milieu of the time as a journalist and writer, can also be placed in this context. His texts often combined political analysis with literary ambition, thus fitting in with the profile of the Berliner Tageblatt. Authors such as Neumann embodied the type of writing intellectual who mediated between feature pages, political commentary, and literary form.

In summary, it can be said that Kurt and Theodor Wolff, the Berliner Tageblatt, articles such as “Ten Years in Nice,” and authors such as Alfred Neumann were part of a shared cultural context. They represent an era in which journalism, literature, and politics were closely intertwined and in which liberal public discourse was understood as a central prerequisite for democratic culture. Looking back, it becomes clear how fragile—and at the same time how significant—this tradition was.

These men were primarily active in the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, with a focus on the period between the German Empire and the Weimar Republic.

Theodor Wolff (1868–1943)

- Active approx. 1900–1933

- Editor-in-chief of the Berliner Tageblatt from 1906 to 1933

- A defining figure of left-wing liberal journalism in the German Empire and the Weimar Republic

- Had to go into exile from the Nazis in 1933

Kurt Wolff (1887–1963)

- Active from around 1910 until the 1950s

- Most important publisher of literary modernism

- Focus of his work: the 1910s and 1920s

- Also emigrated after 1933 (USA)

Alfred Neumann (1895–1952)

- Active primarily in the 1920s and early 1930s

- Journalist and writer of the Weimar Republic

- Wrote political and literary texts

- Emigration after 1933

Shared historical context

- German Empire (1871–1918)

- First World War

- Weimar Republic (1919–1933)

- End of their activities in Germany due to the National Socialists’ seizure of power

Overall, they belonged to Germany’s liberal intellectual public sphere between 1900 and 1933.

-

Èze Village – History, topography, and cultural transformation of a Mediterranean mountain village

Èze Village towers above the sparkling ribbon of the Mediterranean Sea like a silent witness to a complex past. Perched on a steep rocky outcrop on the French Riviera, the village uniquely combines traces of early Ligurian cultures, medieval power struggles, modern fortification policies, and the cultural trends of the Belle Époque. Its development is a prime example of the transformation of Mediterranean settlements from strategic strongholds to symbolic cultural landscapes.

1. The beginnings: Ligurian settlements and Roman spheres of influence

The earliest traces of human presence in the Èze area can be attributed to the Celto-Ligurian tribes who settled in the region around what is now Mont Bastide. The choice of location was motivated by both defensive and economic considerations: the extremely steep topography offered protection from attackers, while the proximity to the sea facilitated trade.

With Roman expansion in Provence, the entire coastal region was integrated into a systematic administrative and transportation system. Although Èze itself was not at the center of Roman urbanity, continuous settlement established itself along the coast, particularly in Èze-sur-Mer. The Roman presence also left behind agricultural techniques such as terraced farming and olive cultivation, which shaped the landscape until modern times.

Èze Village – Cactus Garden 2. Medieval consolidation: between Provence and Savoy

From the High Middle Ages onwards, Èze developed into a fortified village, which was ideal for military purposes due to its location at an altitude of 430 meters. From then on, its history was marked by territorial conflicts: Èze initially belonged to the County of Provence.

From the 14th century onwards, it fell under the rule of the House of Savoy. The conflict between Savoy and France in the 17th century led to multiple changes in strategy and ultimately to its integration into the Kingdom of France.

The medieval streets – now home to artists’ studios and boutiques – were originally designed for defensive purposes. The village functioned as a stone labyrinth intended to confuse attackers. The central fortress, the citadel of Èze, was repeatedly expanded, but fell victim to Louis XIV’s strategic order of destruction in 1706. Today’s platform with the “Jardin Exotique” is a relic of this military past.

3. Modern infrastructure: Fort Révère as part of national defense systems

In the 19th century, Èze once again became the focus of French military planning due to its geographical location. Fort Révère, located in the hinterland above the village, was built after 1870 as part of the so-called Séré de Rivières system – a network of modern fortifications of European significance, created in response to the Franco-Prussian War.

Fort Révère is characterized by: a polygonal layout with casemates, embrasures in all directions, massive walls made of stone and concrete, devices for communication with neighboring coastal and mountain forts.

Although Fort Révère was never involved in combat, it played a role in monitoring the coast and securing the Italian-French border. Today, as a restored monument, it offers one of the most impressive panoramic views of the Riviera and symbolizes an era of European rearmament that changed fundamentally with the First World War.

4. Château Balsan – Riviera romance and sophisticated

The advent of Riviera tourism in the 19th century marked the beginning of a new era for Èze. Château Balsan played a special role in this development. Industrialist Émile Balsan, who came from an influential textile family, acquired the estate and transformed it into a sophisticated retreat.

The château is remarkable for cultural and historical reasons: It was a frequent meeting place for the Parisian and international elite. Coco Chanel, who was closely associated with Émile Balsan in her early life, spent long periods here. It was in Èze that she made the transition from the world of aristocracy and bohemianism to her calling as a designer.

The subsequent conversion of the building into the exclusive Château de la Chèvre d’Or hotel marked another turning point: the Riviera became a luxury destination, while the historic buildings of Èze were integrated into tourist and cultural contexts.

5. Continuity and renewal: From an agricultural society to a cultural landscape

Until the early 20th century, Èze was still heavily agricultural: olive groves, vineyards, terraced farming, and sheep breeding dominated life. It was only with the expansion of modern transport infrastructure—roads, railways along the coast, and later the Corniche Routes—that the village underwent structural change.

The significant combination of historic buildings, an exceptional location, and romantic aesthetics led to Èze becoming a fixture for: artists and writers, botanists (especially because of the exotic garden), historians, and tourists from all over the world.

Today, Èze combines the preservation of its medieval identity with a mixture of arts and crafts, luxury hotels and natural landscape typical of the Côte d’Azur.

6. Concluding remarks

Èze Village is a prime example of the transformative power of historical sites. Its history encompasses: Ligurian origins, medieval power struggles, French and Savoyard territorial politics, modern fortification systems, the sophisticated culture of the Belle Époque and modern cultural tourism.

The Château Balsan and Fort Révère serve as striking anchor points: one embodies the aesthetic and social appeal of the Riviera, the other the strategic importance of the region in an era of geopolitical uncertainty.

Èze is thus not only a picturesque mountain village, but also a living archive of European history—a place where political, cultural, and landscape developments overlap in an extraordinary way.

-

Visit to Villa Kérylos in Beaulieu-sur-Mèr

A visit to Villa Kérylos on the French Riviera is like traveling back in time to the world of the ancient Greeks—but through the eyes of two passionate scholars of the early 20th century.

The visit—atmosphere and impressions

Upon entering the villa, you are greeted by a light-filled courtyard (peristyle) whose marble columns and water basins are immediately reminiscent of the architecture of classical Greek residences. The rooms are richly decorated with frescoes, mosaics, ornate furniture, and everyday objects—many of which were specially crafted based on ancient models, giving visitors the feeling of being in a living archaeology project.

From the open balcony, the view extends across the Mediterranean Sea to the Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat peninsula—a deliberate part of the concept: as in the homes of the ancient Greeks, the sea should always be present.

The owner: Théodore Reinach (1860–1928)

Théodore Reinach was a French scholar, historian, archaeologist, and politician.

He came from the famous Reinach family of bankers and artists, which belonged to France’s intellectual elite.

Reinach was deeply in love with Greek culture and philology. For him, Villa Kérylos was a life project—not as a replica, but as a creative reconstruction of a luxurious residence from the Greek Classical period (2nd–1st century BC).

He used the villa both as a vacation home and as a place of study and representation.

The architect: Emmanuel Pontremoli (1865–1956)

The architect Emmanuel Pontremoli was a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts and later its director. He won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1890 and spent years in Greece and the eastern Mediterranean.

These travels made him a specialist in Hellenistic architecture, which made him the ideal partner for Reinach’s vision. Pontremoli’s approach was extraordinary: he used modern building materials (concrete, iron), but designed each room according to ancient models, and integrated artisans, sculptors, and furniture designers who created new works specifically for the house based on archaeological models.

Historical background – Construction of the villa

- Construction period: 1902–1908

- Style: Hellenistic, inspired by the houses on Delos

- Goal: An “ideal Greek house” – not a copy, but an authentic reinterpretation

- Name: Kérylos means “tern,” a symbol of good luck in Greek mythology

After Reinach’s death in 1928, his family bequeathed the villa to the French Institute, which still manages it today.

Why it’s worth a visit

A tour of Villa Kérylos allows visitors to:

- immerse themselves in the ancient world,

- understand the interplay between science, art, and architecture around 1900,

- and gain insight into the visions of two extraordinary personalities:

a Hellenistic scholar and an architect influenced by Orientalism.

You leave the villa with the impression that you have visited not so much a museum as an ideal Greek house that – for a moment – is filled with life again.

A day at Villa Kérylos

The morning over Beaulieu-sur-Mer is still young as you walk along the narrow coastal road. The sea glistens in a milky blue, and the first rays of sunshine cast a silvery shimmer on the water’s surface. In the distance, you can see the simple, light silhouette of Villa Kérylos – a house that looks as if it has been blown straight from the spirit of antiquity to the coast of the Côte d’Azur.

Even the path leading there has something solemn about it. The bay lies calm, as if holding its breath, as you approach the entrance portal. As you cross the threshold, time suddenly seems to slow down.

In the first courtyard, a feeling of clarity envelops you. The sky above you is like a ceiling painting of pure color, and in the center murmurs a small water basin—the heartbeat of the house. The marble columns cast long shadows that fall across the antique-style mosaics. You feel the noise of the world quietly closing behind you and something else beginning: a silent conversation between you and the spirit of the past.

You wander through the rooms and notice the care that Théodore Reinach and Emmanuel Pontremoli have lavished on every detail. The Andron – once a place for conversations and banquets – welcomes you with cool walls decorated with mythological scenes. You imagine Reinach receiving guests here, scholars and artists immersed in passionate discussions about Greece, while outside the waves crash against the rocks.

In the bedroom, your gaze lingers on a golden border that shimmers in the sunlight. You feel as if this is less a room than a thought, artfully materialized. The bed is designed according to ancient models – simple yet sublime. You wonder if Reinach ever felt here that he was living in two worlds at once: the modern Riviera and ancient Greece.

The library smells of old wood and a hint of the sea. The shelves—delicately crafted—stand as silent witnesses to his studies. Perhaps it was here that he immersed himself in his books while Pontremoli further refined the lines and proportions of the villa in his mind. Two men, united by a vision that came to fruition in these rooms: the dream of a house that does not copy the past, but embodies it.

When you finally reach the balcony, the view opens up to a Mediterranean panorama that seems almost unreal in its beauty. The sea lies like a calm cloth before you, and on the Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat peninsula, the villas glitter like scattered gems. A gentle breeze brushes your cheek, carrying the scent of salt and pine trees. You lean against the railing, and for a moment, the boundary between now and then seems to blur.

Perhaps this is the moment when you truly understand the villa: it is not a museum, but a conversation—between cultures, centuries, people. An ideal built with modern materials and an antique soul. A place that carries the longing not only to preserve beauty, but to live it.

When you leave the villa later and look back once more, it seems to float between the rocks and the sea. Elegant, timeless, a little mysterious. And you know that a part of you remains there, somewhere between the marble columns and the gentle splashing of the fountain, where antiquity came back to life for a moment.