Your basket is currently empty!

Blog

-

The French Riviera of yesteryear

Louis XIV organised the siege of Nice under the command of the Duke of La Feuillade. From 9 to 22 December 1705, the castle of Nice was bombarded relentlessly by 60 cannons and 24 mortars. More than 10,000 bombs and 120,000 cannonballs were fired at the castle during the siege, resulting in between 700 and 800 deaths and injuries. It was not until 4 January 1706 that the Marquis de Caraglio, commander of the citadel of Nice and governor of the county of Nice, surrendered.

-

The Life of Pierre Bonnard

in german below:

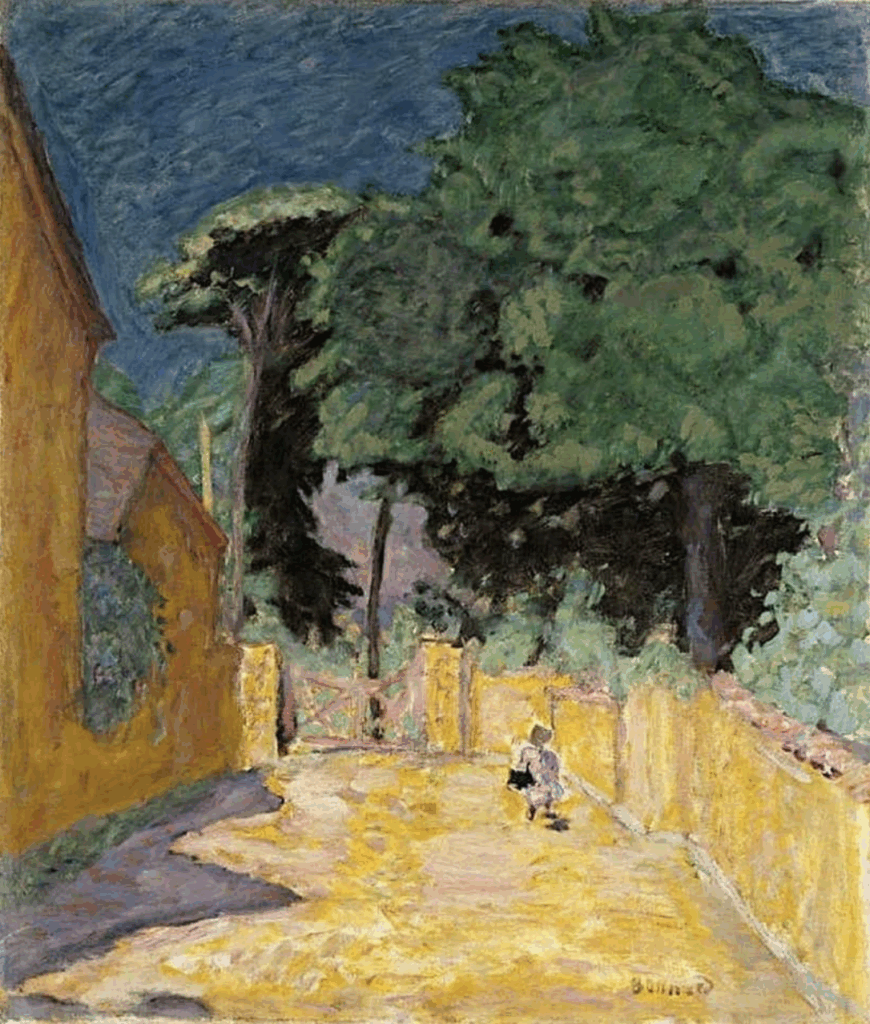

Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) ranks among the outstanding French painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work is characterized by a subtle interplay of light, color, and intimacy, which distinguishes him from the Impressionists and at the same time secures him a special position in the transition to modernism.

Born on October 3, 1867, in Fontenay-aux-Roses near Paris, Bonnard came from a middle-class family. He originally studied law, but was drawn to art from an early age. Together with artist friends such as Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier, and Édouard Vuillard, he joined the artist group “Les Nabis,” which developed new forms of expression beyond the Impressionists after 1888. There he was given the nickname le Nabi très japonard, as he was strongly inspired by Japanese woodblock printing, which was in vogue in Europe around 1900.

Bonnard was less interested in monumental historical themes than in everyday life: street scenes, garden scenes, interiors, and intimate moments. His partner and later wife, Marthe de Méligny, in particular, became his lifelong muse. She appears in numerous paintings, often in bathing or toilet scenes, reflecting Bonnard’s interest in intimacy, domesticity, and the depiction of light on skin and water.His painting technique differed from that of many of his contemporaries: Bonnard rarely worked directly in front of his subject. Instead, he sketched scenes, noted down colors, and later created the paintings in his studio from memory. This gave his pictures a dreamlike quality and an almost poetic blurriness, in which colors took precedence over form.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Bonnard increasingly withdrew from Parisian art life. After stays in Giverny and Vernon, he finally settled on the Côte d’Azur, in Le Cannet near Cannes. There he found inexhaustible motifs in his house and garden. His late works are filled with bright colors, Mediterranean light, and a deep tranquility that expresses his connection to nature.

Although Bonnard was appreciated during his lifetime, he stood in the shadow of artists such as Matisse and Picasso, who radically renewed modern painting. But today, Bonnard’s work is once again highly regarded: his ability to transform the intimate into the universal and his painterly sensibility are considered unique.

Pierre Bonnard died on January 23, 1947, in Le Cannet. His work left its mark on modern painting—not through loud provocations, but through quiet, lasting intensity.

in german:

Das Leben von Pierre Bonnard

Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) zählt zu den herausragenden französischen Malern des späten 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Sein Werk ist geprägt von einem subtilen Spiel aus Licht, Farbe und Intimität, das ihn von den Impressionisten unterscheidet und ihm zugleich eine Sonderstellung im Übergang zur Moderne sichert.

Geboren am 3. Oktober 1867 in Fontenay-aux-Roses bei Paris, stammte Bonnard aus einer bürgerlichen Familie. Ursprünglich studierte er Rechtswissenschaft, doch schon früh zog es ihn zur Kunst. Gemeinsam mit Künstlerfreunden wie Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier und Édouard Vuillard schloss er sich der Künstlergruppe „Les Nabis“ an, die nach 1888 neue Ausdrucksformen jenseits der Impressionisten entwickelte. Dort erhielt er den Beinamen le Nabi très japonard, da er sich stark von der japanischen Farbholzschnittkunst inspirieren ließ, die in Europa um 1900 in Mode war.

Bonnard interessierte sich weniger für monumentale historische Themen als für das Alltägliche: Straßenszenen, Gartenbilder, Interieurs und intime Momente. Besonders seine Partnerin und spätere Ehefrau Marthe de Méligny wurde zu seiner lebenslangen Muse. Sie erscheint in zahlreichen Gemälden, oft in Bad- oder Toilettenszenen, was Bonnards Interesse an Intimität, Häuslichkeit und zugleich an der Darstellung von Licht auf Haut und Wasser spiegelt.

Sein malerisches Verfahren unterschied sich von vielen seiner Zeitgenossen: Bonnard arbeitete selten direkt vor dem Motiv. Stattdessen skizzierte er Szenen, notierte Farben und schuf die Gemälde später im Atelier aus dem Gedächtnis. Das verlieh seinen Bildern eine Traumhaftigkeit und eine beinahe poetische Unschärfe, in der Farben gegenüber der Form Vorrang erhielten.

Mit Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts zog Bonnard sich zunehmend aus dem Pariser Kunstleben zurück. Nach Aufenthalten in Giverny und Vernon ließ er sich schließlich an der Côte d’Azur nieder, in Le Cannet bei Cannes. Dort fand er in seinem Haus und Garten unerschöpfliche Motive. Seine späten Werke sind erfüllt von leuchtenden Farben, mediterranem Licht und einer tiefen Ruhe, die seine Verbindung zur Natur ausdrückt.

Obwohl Bonnard zu Lebzeiten geschätzt wurde, stand er im Schatten von Künstlern wie Matisse und Picasso, die die moderne Malerei radikaler erneuerten. Doch gerade heute wird Bonnards Werk wieder hoch geschätzt: Seine Fähigkeit, das Intime ins Universelle zu überführen, und seine malerische Sensibilität gelten als einzigartig.

Pierre Bonnard starb am 23. Januar 1947 in Le Cannet. Sein Werk hinterließ Spuren in der modernen Malerei – nicht durch laute Provokationen, sondern durch leise, nachhaltige Intensität.

Quellen für Bilder von Pierre Bonnard

- Musée d’Orsay, Paris: umfangreiche Sammlung von Bonnards Arbeiten.

👉 Musée d’Orsay – Pierre Bonnard - Centre Pompidou, Paris: bedeutende Werke der Nabis und der Moderne.

👉 Centre Pompidou - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (The Met Collection Online)

👉 Pierre Bonnard – Met Collection - Tate, London: besitzt mehrere Gemälde und Druckgrafiken.

👉 Pierre Bonnard – Tate - Art Institute of Chicago

👉 Pierre Bonnard – Art Institute of Chicago

- Musée d’Orsay, Paris: umfangreiche Sammlung von Bonnards Arbeiten.

-

Varian Fry – From Berlin to Marseille

in german below:

A life between observation and responsibility

When Varian Fry traveled to Europe aboard the transatlantic liner Bremen in 1935, he was still a young journalist, driven by curiosity, acumen, and an incorruptible eye for the political tensions of his time. Even during the crossing, among diplomats, businesspeople, and emigrants, he heard conversations about Hitler’s job creation programs, currency controls, and growing anti-Semitism. It was a premonition of what awaited him on the continent.

In Berlin, he took up residence at the Hotel-Pension Stern on Kurfürstendamm, a middle-class establishment in the heart of the capital. There, in the breakfast rooms, amid the rustling of newspapers, he conducted his first interviews: politicians who were still wavering between loyalty and inner resistance, business leaders who saw the regime as both a threat and an opportunity, and university lecturers who were torn between academic caution and open ideological loyalty. But Fry didn’t just listen to the voices of the elites. He spoke to shopkeepers who reported boycott actions, to waiters who whispered about guests who had disappeared, to churchgoers who described the pressure on their pastors, and to taxi drivers whose sober cynicism often contained more truth than the official slogans.

Kurfürstendamm became a burning mirror for Fry. Elegant strolling and intimidation by SA men existed side by side. One evening, he got caught up in a street battle: students were protesting against Gleichschaltung, and SA men were dispersing them with boots and batons. Fry, who only wanted to observe, was drawn into the melee. He escaped, but not without injuries – and not without an image of the violence he later described so vividly. Berlin had shown him how deeply ideology, fear, and violence had already penetrated everyday life.

When Fry was sent to Marseille in 1940 on behalf of the Emergency Rescue Committee after the Wehrmacht invaded France, he was prepared. What he had only observed in Berlin now determined his actions: saving people who were on the Gestapo’s blacklists.

Marseille, the last major port in unoccupied France, was a place of both hope and despair. Refugees from all over Europe flocked there—writers, artists, scientists, political dissidents. Fry worked under the guise of a journalist, but his real mission was to organize a rescue operation that was both improvised and life-threatening.

His team was a diverse bunch: Miriam Davenport, the art historian; Mary Jayne Gold, a wealthy American who contributed money and courage; Daniel Bénédite, the French trade unionist who maintained contacts with officials and workers; and later also the young economist Albert Hirschman, who forged passports and organized escape routes. Together, they saved hundreds of people, including Marc Chagall, Heinrich Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Max Ernst, Hannah Arendt, and many others whose work shaped the cultural memory of the 20th century.

The cooperation of the US was ambivalent. The Emergency Rescue Committee had sent him, but Washington kept its distance: officially, it did not want to risk a confrontation with Vichy France or Berlin. Fry therefore operated in a gray area, tolerated but viewed with suspicion. France also showed two faces: individual officials helped quietly, but the Vichy administration cooperated closely with the Germans and handed over refugees. It was only through bribery, forgery, and secret networks that Fry was able to continue his work.

From Marseille, his contacts also extended to the Côte d’Azur: to Nice and Sanary-sur-Mer, where German exiles had been living since the early 1930s—Heinrich and Thomas Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Franz Werfel, Alma Mahler-Werfel, and many others. Fry built on these structures, helping with onward transport, organizing visas and ship passages to Spain and Portugal. In this way, he connected the escape routes along the coast with the rescue routes in Marseille.

But in 1941, Vichy put an end to his work. Fry was expelled, exhausted and plagued by guilt because he could not save everyone. Back in New York, he reported on his experiences and wrote his book Surrender on Demand in 1945, but it went unnoticed for a long time. In the early post-war years, America did not want to be reminded of that period of inaction, when individuals had shown more courage than states. Fry himself lived on the fringes of the intellectual scene, scarred by what he had experienced.

It was not until decades later that he received the recognition he deserved. In 1996, Yad Vashem honored him as the first American with the title “Righteous Among the Nations.” Today, France and Germany also remember the “American Schindler,” who acted not out of political calculation but out of moral clarity.

Varian Fry was both an observer and an actor. In Berlin, he had learned to see behind the facades; in Marseille, he had taken action; in the US, he had fought for remembrance. His life journey—from the salons of the ocean liner Bremen to the Pension Stern on Kurfürstendamm to the improvised rescue offices in Marseille—is testimony to the fact that even a single individual can take responsibility in the face of violence.

in german:

Varian Fry – Von Berlin nach Marseille

Ein Leben zwischen Beobachtung und Verantwortung

Als Varian Fry 1935 an Bord des Transatlantikliners Bremen nach Europa reiste, war er noch ein junger Journalist, getrieben von Neugier, Scharfsinn und einem unbestechlichen Blick für die politischen Spannungen seiner Zeit. Schon auf der Überfahrt, zwischen Diplomaten, Geschäftsleuten und Emigranten, hörte er Gespräche über Hitlers Arbeitsbeschaffungsprogramme, über Devisenkontrollen und über den wachsenden Antisemitismus. Es war eine Vorahnung dessen, was ihn auf dem Kontinent erwartete.

In Berlin bezog er Quartier in der Hotel-Pension Stern am Kurfürstendamm, einem bürgerlichen Haus im Herzen der Hauptstadt. Dort, in den Frühstücksräumen, beim Rascheln der Zeitungen, führte er seine ersten Interviews: Politiker, die noch zwischen Loyalität und innerem Widerstand schwankten, Wirtschaftsführer, die im Regime ebenso Bedrohung wie Chance sahen, und Universitätsdozenten, die zwischen akademischer Vorsicht und offener Ideologietreue lavierten. Doch Fry hörte nicht nur den Stimmen der Eliten zu. Er sprach mit Ladenbesitzern, die von Boykottaktionen berichteten, mit Kellnern, die im Flüsterton von verschwundenen Gästen erzählten, mit Kirchenbesuchern, die den Druck auf ihre Pfarrer schilderten, und mit Taxichauffeuren, deren nüchterner Zynismus oft mehr Wahrheit enthielt als die offiziellen Parolen.

Der Kurfürstendamm wurde für Fry zu einem Brennspiegel. Elegantes Flanieren und Einschüchterung durch SA-Männer existierten nebeneinander. Eines Abends geriet er in eine Straßenschlacht: Studenten protestierten gegen die Gleichschaltung, SA-Männer trieben sie mit Stiefeln und Schlagstöcken auseinander. Fry, der nur beobachten wollte, wurde in das Getümmel hineingezogen. Er entkam, aber nicht ohne Verletzungen – und nicht ohne ein Bild jener Gewalt, die er später so eindringlich beschrieb. Berlin hatte ihm gezeigt, wie tief Ideologie, Angst und Gewalt bereits in den Alltag eingedrungen waren.

Als Fry 1940, nach dem Einmarsch der Wehrmacht in Frankreich, im Auftrag des Emergency Rescue Committee nach Marseille entsandt wurde, war er vorbereitet. Was er in Berlin nur beobachtet hatte, bestimmte nun sein Handeln: Menschen retten, die auf den schwarzen Listen der Gestapo standen.

Marseille, der letzte große Hafen im unbesetzten Frankreich, war ein Ort der Hoffnung und Verzweiflung zugleich. Flüchtlinge aus ganz Europa strömten dorthin – Schriftsteller, Künstler, Wissenschaftler, politische Dissidenten. Fry arbeitete unter dem Deckmantel eines Journalisten, doch sein eigentlicher Auftrag war die Organisation einer Rettungsmaschine, die zugleich improvisiert und lebensgefährlich war.

Sein Team war bunt zusammengesetzt: Miriam Davenport, die Kunsthistorikerin; Mary Jayne Gold, eine wohlhabende Amerikanerin, die Geld und Mut beisteuerte; Daniel Bénédite, der französische Gewerkschafter, der Kontakte zu Beamten und Arbeitern hielt; später auch der junge Ökonom Albert Hirschman, der Pässe fälschte und Fluchtwege organisierte. Gemeinsam retteten sie Hunderte – unter ihnen Marc Chagall, Heinrich Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Max Ernst, Hannah Arendt und viele andere, deren Werk das kulturelle Gedächtnis des 20. Jahrhunderts prägt.

Die Kooperation der USA war ambivalent. Das Emergency Rescue Committee hatte ihn entsandt, doch Washington hielt Distanz: Offiziell wollte man keine Konfrontation mit Vichy-Frankreich oder Berlin riskieren. Fry agierte daher im Graubereich, geduldet, aber misstrauisch beäugt. Auch Frankreich zeigte zwei Gesichter: Einzelne Beamte halfen im Stillen, doch die Vichy-Administration kooperierte eng mit den Deutschen und lieferte Flüchtlinge aus. Nur durch Bestechungen, Fälschungen und heimliche Netzwerke gelang es Fry, seine Arbeit fortzuführen.

Von Marseille aus reichten seine Kontakte auch an die Côte d’Azur: nach Nizza und nach Sanary-sur-Mer, wo bereits seit den frühen 1930er Jahren deutsche Exilanten lebten – Heinrich und Thomas Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Franz Werfel, Alma Mahler-Werfel und viele andere. Fry knüpfte an diese Strukturen an, half beim Weitertransport, organisierte Visa und Schiffspassagen nach Spanien und Portugal. So verband er die Fluchtwege an der Küste mit den Rettungsrouten in Marseille.

Doch 1941 setzte Vichy seiner Arbeit ein Ende. Fry wurde ausgewiesen, ausgelaugt und von Schuldgefühlen geplagt, weil er nicht alle retten konnte. Zurück in New York berichtete er, schrieb 1945 sein Buch Surrender on Demand, doch es blieb lange unbeachtet. Amerika wollte in den ersten Nachkriegsjahren nicht erinnert werden an jene Zeit der Untätigkeit, als Einzelne mehr Mut gezeigt hatten als Staaten. Fry selbst lebte am Rande der intellektuellen Szene, gezeichnet von dem, was er erlebt hatte.

Erst Jahrzehnte später erhielt er die Anerkennung, die ihm gebührte. 1996 ehrte ihn Yad Vashem als ersten Amerikaner mit dem Titel „Gerechter unter den Völkern“. Auch in Frankreich und Deutschland erinnert man heute an den „amerikanischen Schindler“, der nicht aus politischem Kalkül, sondern aus moralischer Klarheit handelte.

Varian Fry war Beobachter und Akteur zugleich. In Berlin hatte er gelernt, hinter die Fassaden zu sehen, in Marseille hatte er gehandelt, in den USA hatte er für Erinnerung gestritten. Sein Lebensweg – von den Salons des Linienschiffs Bremen über die Pension Stern am Kurfürstendamm bis zu den improvisierten Rettungsbüros in Marseille – ist ein Zeugnis dafür, dass auch ein Einzelner im Angesicht der Gewalt Verantwortung übernehmen kann.

Photo:Varian Fry in Marseille. Frankreich, 1940–1941 in Marseille. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Annette Fry

-

Leseabende in Sanary — die Exil-Salonkunst

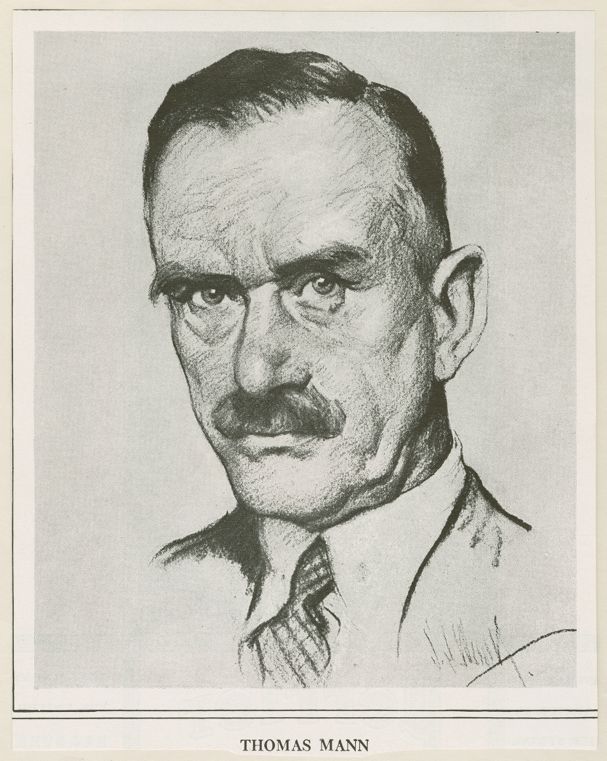

Thomas Mann und die Exil-Salonkunst

in english below:

Thomas Mann und die kleine Exil-Salonkunst

Im Sommer 1933, kurz nach der Flucht vieler deutscher Intellektueller vor dem NS-Regime, veränderte sich das Leben in dem einst verschlafenen Fischerdorf Sanary-sur-Mer an der Côte d’Azur. Unter den neu Angekommenen waren Thomas Mann und seine Familie; bald bildete sich um die Villen der Emigranten ein enges, kultiviertes Netzwerk aus Schriftstellern, Kritikern und Künstlern. In diesem Milieu etablierten sich die berüchtigten Lese- und Gesprächsabende — zwanglose, zugleich hochintellektuelle Zusammenkünfte, die Thomas Mann, sein Bruder Heinrich, René Schickele, Lion Feuchtwanger, Julius Meier-Graefe und andere regelmäßig besuchten oder selbst als Vortragende gestalteten. Diese Abende waren weder akademische Tagungen noch rein private Plauderstunden: sie verbanden Vorlesung, gegenseitige Kritik und politischen Austausch in einer Zeit, in der beides — Kunst und Öffentlichkeit — unter Druck geraten war. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+1

Räumliche und soziale Bühne

Die Lesungen fanden häufig in den Gärten und Salons der großen Villen statt — etwa in der von Thomas Mann bewohnten „Villa La Tranquille“ oder im Haus der Feuchtwangers und bei René Schickele. Hier herrschte eine intime, fast familiäre Atmosphäre: ein Kreis ausgewählter Gäste, Tee oder Abendessen, ein Tisch oder ein Sessel als „Pult“ für den Vortragenden. Die physische Nähe der Häuser in Sanary sowie die starke Vernetzung der Emigranten machten die Stadt zu einem Ort, an dem private Salonpraxis und politisches Exil sich überlagerten. literaturportal-bayern.de+1Inhalte und Gesprächsgegenstände

Die Themen der Abende waren vielfältig, aber zwei Linien ziehen sich wie ein roter Faden durch die Berichte und Erinnerungen: erstens die literarische Arbeit (Vorlesen aus Romanen, Erzählungen oder Essays, Diskussion von Werken in Arbeit), zweitens die Politik des Exils (die Lage in Deutschland, die Frage nach Widerstand, Verantwortung und kultureller Identität). Thomas Mann selbst las gelegentlich aus eigenen Texten oder Entwürfen— der Akt des Vorlesens war für ihn ein Ritual, das Normalität stiftete und gleichzeitig das Publikum unmittelbar an der Entstehung literarischer Form teilhaben ließ. Andere Vortragende — etwa René Schickele oder Lion Feuchtwanger — brachten Texte, feuilletonistische Reflexionen oder polemische Stellungnahmen zur gegenwärtigen politischen Lage ein. Kritik und Retrofit (formale Hinweise, stilistische Debatten) mischten sich mit ernsten Debatten über Exilpolitik, Publikationsmöglichkeiten und die moralische Verpflichtung der Schriftsteller gegenüber den Vertriebenen und den zurückgebliebenen Lesern. De Gruyter Brill+1Welche Rollen spielten die genannten Personen konkret?

René Schickele galt als Brückenfigur zwischen der deutsch-französischen Kulturwelt und las sowohl literarische Texte als auch kulturkritische Essays. Julius Meier-Graefe, Kunstkritiker und weithin respektierter Intellektueller, trug kunsttheoretische Betrachtungen vor und kommentierte die kulturelle Lage Europas. Lion Feuchtwanger, ein aktiver politischer Intellektueller, nutzte die Runden oft, um über Publikationsstrategien, Leihnetzwerke und die Notwendigkeit kollektiven Handelns zu sprechen. Heinrich Mann, stets politisch engagiert, brachte historische und öffentliche Perspektiven ein — die Brüder Thomas und Heinrich ergänzten einander hier oft: der eine literarisch, der andere programmatisch-politisch. Diese differenzierten Beiträge ließen die Abende zu einem Ort werden, an dem sowohl Formfragen (Ästhetik, Stil) als auch Existenzfragen (Flucht, Publikation, Exilerfahrung) verhandelt wurden. literaturportal-bayern.de+1Gibt es Aufzeichnungen der Gespräche?

Zu den Lesungen selbst existieren keine bekannten systematischen Ton- oder Filmaufzeichnungen der privaten Salonabende in Sanary; es handelt sich zumeist um mündliche, geschlossene Runden, deren Protokolle allenfalls bruchstückhaft in Briefen, Tagebuchnotizen oder späteren Erinnerungen auftauchen. Die wichtigste Quelle für die Rekonstruktion dieser Abende sind deshalb persönliche Briefe, Tagebücher, Memoiren und Korrespondenzen der Beteiligten sowie Nachlässe in Archiven (z. B. das Thomas-Mann-Archiv in Zürich, Feuchtwanger-Sammlungen, verschiedene Universitätsarchive), die Manuskripte, Skizzen und gelegentlich schriftliche Notizen zu Vorträgen enthalten. Wer die Diskussionen „nachhört“, tut dies durch sorgfältiges Studium dieser Dokumente — die Lesarten bleiben dabei notwendigerweise selektiv und rekonstruierend. Thomas-Mann-Archiv+1Tonaufnahmen Thomas Manns existieren zwar (etwa frühe Aufnahmen und später die BBC-Ansprachen „Deutsche Hörer!“), doch diese dokumentieren öffentliche Reden und Rundfunksendungen — nicht die privaten Leseabende in Sanary. Für die Abende selbst muss man sich auf schriftliche Quellen stützen. Wikipedia+1

Quellenlage und Forschungsmöglichkeiten

Wer heute mehr über die Leseabende wissen will, findet wertvolle Hinweise in lokalen Sammlungen (Gemeindearchiv Sanary, touristische Dokumentationen zur „Stadt des Exils“), in den großen Nachlass-Archiven (Thomas-Mann-Archiv ETH Zürich, Feuchtwanger-Papers, Nachlässe bei Universitäten) und in wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten zur Exilliteratur und zur deutsch-französischen Emigrationsgemeinschaft der 1930er Jahre. Sekundärliteratur, Konferenzbeiträge und Monographien rekonstruieren die soziale Praxis dieser Salons und ordnen die Gespräche in die größere Geschichte des Exils ein. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+2nomadit.co.uk+2Normalität als Widerstandsform

Die Leseabende in Sanary erscheinen, bei aller Intellektualität, auch als ein Akt des Alltags: das wiederholte Vorlesen, die Diskussion über Form, die Pflege ästhetischer Rituale – all das war mehr als Kulturpflege; es war ein Widerstand gegen die Zerstörung einer kulturellen Ordnung. In den kleinen Salons von Sanary verwoben sich Literatur und politisches Bewusstsein, und die Abende selbst wurden zu Zeugnissen jener fragile Normalität, die Exilanten suchten und zugleich verteidigten. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+1

Wichtige Archiv- und Nachlassquellen

Archiv / Sammlung Relevante Bestände / Materialien Hinweise zur Einsicht Thomas-Mann-Archiv, ETH Zürich Umfasst Manuskripte, Typoskripte, Korrespondenzen (ca. 16 000 Briefe, plus Briefe von und an Katia, Töchter etc.) thomas-mann-gesellschaft.de+2Thomas-Mann-Archiv+2 Die Metadaten und Beschreibungen vieler Briefe sind online verfügbar; digitale Handschriften werden zunehmend zugänglich gemacht (teilweise nur im Lesesaal) Thomas-Mann-Archiv+1 Feuchtwanger-Nachlass / Feuchtwanger Memorial Library Briefe, Tagebuchaufzeichnungen, Gästelisten, mögliche Notizen zu Salonrunden Die Feuchtwanger Archives sind Teil des Netzwerks literarischer Forschungseinrichtungen (z. B. in den USA) thomasmanninternational.com+1 Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach Allgemeine Quellen zur Exilliteratur, Korrespondenzen von Emigranten, Sammlungen zu Meier-Graefe etc. Als großes Literaturarchiv führt Marbach vielfältige Brief- und Manuskriptbestände, auch zu Exilautoren thomasmanninternational.com+1 Heinrich-Mann-Archiv / Akademie der Künste, Berlin Briefe, Manuskripte, Materialien von Heinrich Mann Teil des Thomas-Mann-International / Netzwerks der Mann-Archive thomasmanninternational.com+1 Thomas Mann Collection, Yale University Manuskripte, Briefe und Dokumente (in Ergänzung zu den Beständen in Zürich) archives.yale.edu Für Forschende mit Zugang zu US-Archiven relevant

Exemplarische Fundstücke & Exzerpte

Nachfolgend einige konkrete Nachweise, die (teilweise) Ausblicke auf die Sanary-Leseabende und ihr Umfeld ermöglichen:

- Rene Schickele, Tagebuch 8. Mai 1933

Schickele notiert eine Begegnung mit Thomas Mann: „Er sieht schlecht aus … sehr bedrückt … Für Heinrich Mann bedeutet die Verbannung … keine große Veränderung … Thomas … ist … aus allen Himmeln gefallen.“

Damit gibt Schickele einen Stimmungsbeitrag zur frühen Exilphase ab. literaturportal-bayern.de - Thomas Mann — Brief an Hermann Hesse, 31. Juli 1933

In diesem Brief äußert Thomas Mann seine inneren Konflikte mit der Exilsituation: „Ich habe meinen Kampf durchgekämpft. Es kommen freilich immer noch Augenblicke, in denen ich mich frage: warum eigentlich? … Es ginge nicht, ich würde verkommen …“

Der Brief belegt, wie literarisches Schaffen in Sanary mit existenzieller Unsicherheit gekoppelt war. literaturportal-bayern.de - Monika Mann, Erinnerungen

Monika Mann schildert, wie ihr Vater in der Villa La Tranquille Leseabende fortsetzte, die bereits in Bandol begonnen worden waren, und dass neben ihm auch Schickele, Feuchtwanger und Heinrich Mann Texte vortrugen. literaturportal-bayern.de+2literaturportal-bayern.de+2 - Sanary: “Villa Valmer” — Feuchtwanger’s Salon

Nachdem Thomas Mann Sanary verlassen hatte, wurde die Villa Valmer zum Treffpunkt literarischer Kreise, mit Lesungen und Gedankenaustausch. Marta Feuchtwanger organisierte Teegesellschaften, zu denen bis zu sechzig Gäste eingeladen wurden. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+1 - Sekundärliteratur / Exilstudien

In der Studie Sanary – Deutsche Literatur im Exil ist ein Brief von Schickele an Thomas Mann vom 17. April 1933 erwähnt, der im Kontext der Exilvermittlung steht. SpringerLink

In Exile in Paradise: A Literary History of Sanary-sur-Mer werden die intellektuellen Netzwerke, die institutionelle Infrastruktur der Exilkolonie und die literarische Praxis in Sanary aus kulturhistorischer Sicht analysiert. nomadit.co.uk+2nomadit.co.uk+2 - Literaturportal Bayern

Dort heißt es: „In der Villa La Tranquille setzt Thomas Mann seine bereits in Bandol begonnen Leseabende fort. … Hier tragen Autoren wie Rene Schickele, Lion Feuchtwanger, sein Bruder Heinrich aber auch er selbst Texte vor.“ literaturportal-bayern.de

René Schickele

in english:

Reading evenings in Sanary — the art of the salon in exile

Thomas Mann and the small art of exile salons

In the summer of 1933, shortly after many German intellectuals fled the Nazi regime, life changed in the once sleepy fishing village of Sanary-sur-Mer on the Côte d’Azur. Among the new arrivals were Thomas Mann and his family; soon a close-knit, cultured network of writers, critics, and artists formed around the villas of the emigrants. This milieu gave rise to the infamous reading and discussion evenings—casual yet highly intellectual gatherings that Thomas Mann, his brother Heinrich, René Schickele, Lion Feuchtwanger, Julius Meier-Graefe, and others regularly attended or even organized themselves as speakers. These evenings were neither academic conferences nor purely private chats: they combined lectures, mutual criticism, and political exchange at a time when both art and public life were under pressure. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+1

Spatial and social stage

The readings often took place in the gardens and salons of large villas—such as Thomas Mann’s “Villa La Tranquille,” the Feuchtwangers’ house, and René Schickele’s home. These venues fostered an intimate, almost familial atmosphere: a circle of select guests, tea or dinner, a table or armchair serving as a “lectern” for the speaker. The physical proximity of the houses in Sanary and the strong network of emigrants made the town a place where private salon practice and political exile overlapped. literaturportal-bayern.de+1Contents and topics of conversation

The topics of the evenings were varied, but two themes run like a thread through the reports and memories: first, literary work (readings from novels, stories, or essays, discussion of works in progress); second, the politics of exile (the situation in Germany, the question of resistance, responsibility, and cultural identity). Thomas Mann himself occasionally read from his own texts or drafts—for him, the act of reading aloud was a ritual that created normality and at the same time allowed the audience to participate directly in the creation of literary form. Other speakers—such as René Schickele and Lion Feuchtwanger—contributed texts, feuilletonistic reflections, or polemical statements on the current political situation. Criticism and retrofitting (formal references, stylistic debates) mingled with serious debates about exile politics, publication opportunities, and the moral obligation of writers toward displaced persons and readers who had been left behind. De Gruyter Brill+1What specific roles did the individuals mentioned play?

René Schickele was regarded as a bridge between German and French cultural circles and read both literary texts and cultural criticism essays. Julius Meier-Graefe, art critic and widely respected intellectual, presented art theory observations and commented on the cultural situation in Europe. Lion Feuchtwanger, an active political intellectual, often used the gatherings to discuss publication strategies, lending networks, and the need for collective action. Heinrich Mann, always politically engaged, contributed historical and public perspectives—the brothers Thomas and Heinrich often complemented each other here: one literarily, the other programmatically and politically. These nuanced contributions made the evenings a place where both formal questions (aesthetics, style) and existential questions (flight, publication, exile experience) were negotiated. literaturportal-bayern.de+1Are there any recordings of the conversations?

There are no known systematic audio or film recordings of the private salon evenings in Sanary; these were mostly closed, oral gatherings, with only fragmentary accounts appearing in letters, diary entries, or later memoirs. The most important sources for reconstructing these evenings are therefore personal letters, diaries, memoirs, and correspondence of those involved, as well as estates in archives (e.g., the Thomas Mann Archive in Zurich, Feuchtwanger collections, various university archives), which contain manuscripts, sketches, and occasionally written notes on lectures. Anyone who “listens in” on the discussions does so by carefully studying these documents—the interpretations necessarily remain selective and reconstructive. Thomas Mann Archive+1Although audio recordings of Thomas Mann exist (such as early recordings and later the BBC addresses “Deutsche Hörer!”), these document public speeches and radio broadcasts—not the private reading evenings in Sanary. For the evenings themselves, one must rely on written sources. Wikipedia+1

Sources and research opportunities

Anyone who wants to know more about the reading evenings today will find valuable information in local collections (Sanary municipal archives, tourist documentation on the “city of exile”), in the major estate archives (Thomas Mann Archive at ETH Zurich, Feuchtwanger Papers, bequests at universities) and in academic works on exile literature and the German-French emigrant community of the 1930s. Secondary literature, conference papers, and monographs reconstruct the social practice of these salons and place the conversations in the larger history of exile. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+2nomadit.co.uk+2Normality as a form of resistance

Despite their intellectual nature, the reading evenings in Sanary also appear to be an act of everyday life: the repeated reading aloud, the discussion of form, the cultivation of aesthetic rituals – all this was more than just cultural preservation; it was resistance against the destruction of a cultural order. In the small salons of Sanary, literature and political awareness intertwined, and the evenings themselves became testimonies to the fragile normality that exiles sought and defended at the same time. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+1

Exemplary findings & excerpts

Below are some specific examples that provide (partial) insights into the Sanary reading evenings and their context:

- René Schickele, Diary, May 8, 1933

Schickele notes an encounter with Thomas Mann: “He looks terrible … very depressed … For Heinrich Mann, exile means … no great change … Thomas … has … fallen from heaven.” Schickele thus contributes to the mood of the early exile phase. literaturportal-bayern.de - Thomas Mann — Letter to Hermann Hesse, July 31, 1933

In this letter, Thomas Mann expresses his inner conflicts with his situation in exile: “I have fought my battle. Of course, there are still moments when I ask myself: why, actually? … It wouldn’t work, I would degenerate …”The letter shows how literary creativity in Sanary was linked to existential uncertainty. literaturportal-bayern.de - Monika Mann, Memories

Monika Mann describes how her father continued the reading evenings at Villa La Tranquille that had already begun in Bandol, and that Schickele, Feuchtwanger, and Heinrich Mann also recited texts alongside him. literaturportal-bayern.de+2literaturportal-bayern.de+2 - Sanary: “Villa Valmer” — Feuchtwanger’s Salon

After Thomas Mann left Sanary, Villa Valmer became a meeting place for literary circles, with readings and exchanges of ideas. Marta Feuchtwanger organized tea parties to which up to sixty guests were invited. Office de Tourisme Sanary sur Mer+1 - Secondary literature / Exile studies

The study Sanary – Deutsche Literatur im Exil (Sanary – German Literature in Exile) mentions a letter from Schickele to Thomas Mann dated April 17, 1933, which relates to the mediation of exile. SpringerLinkExile in Paradise: A Literary History of Sanary-sur-Mer analyzes the intellectual networks, institutional infrastructure of the exile colony, and literary practice in Sanary from a cultural-historical perspective. nomadit.co.uk+2nomadit.co.uk+2 - Literature Portal Bavaria

It states: “At Villa La Tranquille, Thomas Mann continues the reading evenings he began in Bandol. … Here, authors such as Rene Schickele, Lion Feuchtwanger, his brother Heinrich, and Mann himself recite texts.” literaturportal-bayern.de

- Rene Schickele, Tagebuch 8. Mai 1933

-

APÉRO AT TWELVE

ABOUT TWO PEOPLE WHO MOVED TO FRANCE TO LIVE

A book for all fans of France. And a wealth of experience for anyone who wants to follow in the author’s footsteps and make their dream of emigrating to France a reality.

„Aufgeben ist keine Option, wenn es darum geht, sich seinen Traum zu erfüllen.“

– Ines Sachs –Author Ines Sachs and her husband decide to leave Germany behind and live a life in the sunshine of southern France. In this book, she describes her emigration with affection and a great deal of humor: how the dream becomes a plan (it’s no coincidence that she is married to a project manager), the minor difficulties and major hurdles that need to be overcome, and finally the arrival in their new home, which does not go as smoothly as they had imagined.

-

La Colombe d’Or – Inn, Myth, Museum

When you stroll through the medieval village of Saint-Paul-de-Vence today, along the narrow streets, past galleries and bougainvillea-covered facades, a place of almost mythical status opens up at the end of the city wall: La Colombe d’Or. Neither a glamorous grand hotel nor a simple country inn, but a cross between the two – and at the same time a living museum where art and the art of living have been merging for almost a century.

The beginnings – Paul Roux and his “Golden Dove”

The establishment was opened in 1920 by Paul Roux, a former farmer’s son. Initially, it was a small café with just a few tables, which quickly became a meeting place for villagers and travelers. Roux, a man of charisma and warmth, knew how to attract people. Together with his wife Titine, he ran the establishment in a family atmosphere, where the food was simple, Provençal, and generous. Soon, painters and writers began to discover the Côte d’Azur for themselves – and found in the “Golden Dove” a refuge that was more than just an inn.

Artists as guests – from Picasso to Calder

After World War II in particular, La Colombe d’Or became a center for the avant-garde. Henri Matisse, who worked in Nice and Vence, is said to have stayed there, as did Marc Chagall, who settled in Saint-Paul. Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Joan Miró found their place here, as did Alexander Calder, who created the famous mobile sculpture tree in the garden.

According to legend, some artists paid their bills with drawings or canvases – not out of poverty, but as a spontaneous gesture. This resulted in a collection that still adorns the walls of the house today: a mosaic of handwriting, colors, and shapes that can be viewed almost casually over dinner.

The guest book as a chronicle

The guest book of La Colombe d’Or is less a register than a miniature chronicle of the 20th century. It contains dedications by Pablo Picasso, who left behind sketches of bullfighting scenes, and entries by Jacques Prévert, who lived in Saint-Paul for a long time and expressed his gratitude for the place in poetic words. The American writer James Baldwin, who found refuge in Provence, is also listed.

The entries oscillate between quickly jotted sketches—heads, lines, a few birds—and lyrical messages: Chagall wrote of the “blue air above the olives,” while Calder drew a balance of forms with just a few strokes. The guest book is a mirror of bohemian life: informal but full of intensity, a documented dialogue between guests and host.

Myth and continuity

What makes La Colombe d’Or unique to this day is the combination of everyday life and world art. Here, original works hang next to the kitchen, above the tables, on the staircases – not in a museum with white distance, but in the midst of life. You eat aioli or daube provençale under a Miró, you drink wine in the shadow of Léger’s bold colors.

Film stars and intellectuals also found their place here: Orson Welles, Yves Montand and Simone Signoret, Sophia Loren, later Roger Moore and Charlie Chaplin. In the 1950s and 60s, the establishment became a symbol of the blend of glamour and intimacy that characterized the Côte d’Azur.

To this day, La Colombe d’Or has remained family-owned and run by the descendants of Paul Roux. That’s what makes it so magical: it’s not a sterile hotel chain, but an organism that has grown over generations and remains true to itself.

Conclusion

La Colombe d’Or is more than a hotel or restaurant: it is a narrative woven from stone, color, and memory. Its historical development mirrors the evolution of art in the 20th century, and its guests represent the longing for a place where food, friendship, and art merge into one. The guest book remains the intimate heart of this story—a poetic archive that lifts the “golden dove” into the skies of cultural history.

in german:

La Colombe d’Or – Gasthaus, Mythos, Museum

Wenn man heute durch das mittelalterliche Dorf Saint-Paul-de-Vence schreitet, die engen Gassen entlang, vorbei an Galerien und Bougainvillea-bewachsenen Fassaden, öffnet sich am Ende der Stadtmauer ein Ort, der fast mythischen Rang besitzt: La Colombe d’Or. Weder ein mondänes Grandhotel noch ein schlichtes Landgasthaus, sondern eine Kreuzung aus beidem – und zugleich ein lebendes Museum, in dem Kunst und Lebenskunst seit fast einem Jahrhundert miteinander verschmelzen.

Die Anfänge – Paul Roux und seine „Goldene Taube“

Das Haus wurde 1920 von Paul Roux, einem ehemaligen Bauernsohn, eröffnet. Zunächst war es ein kleines Café mit wenigen Tischen, das schnell zu einem Treffpunkt für Dorfbewohner und Durchreisende wurde. Roux, ein Mann mit Charisma und Wärme, verstand es, Menschen anzuziehen. Mit seiner Frau Titine führte er das Haus in familiärer Atmosphäre, wo das Essen schlicht, provenzalisch und großzügig war. Schon bald begannen Maler und Schriftsteller, die Côte d’Azur für sich zu entdecken – und fanden in der „Goldenen Taube“ ein Refugium, das mehr war als ein Gasthaus.

Künstler als Gäste – von Picasso bis Calder

Besonders nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg wurde La Colombe d’Or zu einem Zentrum der Avantgarde. Henri Matisse, der in Nizza und Vence arbeitete, soll ebenso eingekehrt sein wie Marc Chagall, der sich in Saint-Paul niederließ. Georges Braque, Fernand Léger und Joan Miró fanden hier ebenso ihren Platz wie Alexander Calder, der den berühmten mobilen Skulpturenbaum im Garten schuf.

Der Legende nach bezahlten manche Künstler ihre Rechnungen mit Zeichnungen oder Leinwänden – nicht aus Armut, sondern aus spontaner Geste. So entstand eine Sammlung, die bis heute die Wände des Hauses schmückt: ein Mosaik an Handschriften, Farben und Formen, das man beim Abendessen fast beiläufig betrachten kann.

Das Gästebuch als Chronik

Das Gästebuch von La Colombe d’Or ist weniger ein Register als eine Chronik des 20. Jahrhunderts in Miniatur. Darin finden sich Widmungen von Pablo Picasso, der skizzenhaft Stierkampfszenen hinterließ, oder Einträge von Jacques Prévert, der lange Zeit in Saint-Paul lebte und in poetischen Worten seine Dankbarkeit für den Ort notierte. Auch der amerikanische Schriftsteller James Baldwin, der in der Provence Zuflucht fand, ist verzeichnet.

Die Einträge oszillieren zwischen rasch hingeworfenen Skizzen – Köpfe, Linien, ein paar Vögel – und lyrischen Botschaften: Chagall schrieb von der „blauen Luft über den Oliven“, während Calder mit wenigen Strichen eine Balance von Formen zeichnete. Das Gästebuch ist ein Spiegel der Boheme: informell, aber voller Intensität, ein dokumentierter Dialog zwischen Gästen und Gastgeber.

Mythos und Kontinuität

Was La Colombe d’Or bis heute einzigartig macht, ist die Verbindung von Alltäglichkeit und Weltkunst. Hier hängen Originalwerke neben der Küche, über den Tischen, an den Treppenaufgängen – nicht wie in einem Museum mit weißer Distanz, sondern inmitten des Lebens. Man isst Aioli oder Daube provençale unter einem Miró, man trinkt Wein im Schatten von Légers kräftigen Farben.

Auch Filmstars und Intellektuelle fanden hier ihren Ort: Orson Welles, Yves Montand und Simone Signoret, Sophia Loren, später Roger Moore oder Charlie Chaplin. In den 1950er- und 60er-Jahren wurde das Haus zu einem Symbol für jene Mischung aus Glamour und Intimität, die die Côte d’Azur prägte.

Bis heute ist La Colombe d’Or in Familienbesitz geblieben – geführt von den Nachkommen Paul Roux’. Das macht seinen Zauber aus: keine sterile Hotelkette, sondern ein über Generationen gewachsener Organismus, der sich selbst treu bleibt.

Fazit

La Colombe d’Or ist mehr als ein Hotel oder Restaurant: Es ist eine Erzählung aus Stein, Farbe und Erinnerung. Seine historische Entwicklung spiegelt die Bewegung der Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert, seine Gäste repräsentieren die Sehnsucht nach einem Ort, an dem Essen, Freundschaft und Kunst zu einer Einheit verschmelzen. Das Gästebuch bleibt das intime Herz dieser Geschichte – ein poetisches Archiv, das die „goldene Taube“ in die Lüfte der Kulturgeschichte hebt.