Your basket is currently empty!

Tag: Klaus Kampe

-

Preprint from “German Emigrants”

Fates spanning three centuries – by Klaus Kampe

Chapter 4 – Land of Promise

Conrad Weiser, the Quakers, and the Price of Freedom

“I have learned two languages—

that of the fathers, who count everything,

and that of the Iroquois, who tell everything.

The truth lies somewhere in between.”

— Conrad Weiser, letter to his wife Anna Eva, ca. 1737- The Legacy of the First Generation

When the second generation of Germans in Pennsylvania came of age, the wilderness was no longer an enemy, but property. Land was the new gospel. Those who had it were considered blessed; those who lost it were considered punished.

The first immigrants had received the land as a gift—free, open, boundless. But now every claim had to be documented with papers, seals, and boundary stones. And that’s when a new kind of war began: quiet, legal, fueled by greed, ignorance, and mistrust.

Johann Conrad Weiser Sr., who had once started out as a simple settler in Germantown, soon found himself in conflict with the Crown of New York. German families were promised land in the Schoharie Valley, but when they arrived, it had already been sold – to speculators who had obtained their papers from London, The Hague, or even Frankfurt. The German settlers called it the “land of false deeds.”

“They gave us forest land that we bought with blood, and called us disobedient because we couldn’t read the contract.”

– From the “Schoharie Petition,” 1718- The dealers in land

During those years, a name appeared in the colonial administration’s files that soon became a curse word among Germans: Johannes Tschudi. A man from Zurich, once a notary, then a commercial agent, and finally a land commissioner—and, as was later discovered, a skilled forger.

Tschudi was one of those borderline figures between legitimacy and fraud that the colonial era produced in abundance. He had seals and coats of arms that looked deceptively genuine and issued settlement certificates that purportedly came from the governor of Pennsylvania. For a fee of “two Louis d’or per family,” he promised 200 acres of land, plus the right to timber, grazing, and tax exemption for seven years.

A surviving pamphlet written by him states:

“News of the fertile land of Penn-Sylvania, where milk, honey, and justice flow, and every man may be his own king.”

The sheet circulated between Frankfurt, Strasbourg, Ulm, and Zurich. Many believed it—not least because it was printed on parchment with a colonial seal that had been forged in London. Those who registered received a map with plots of land marked on it—often in areas that did not even exist.

A descendant of the Braun family from the Palatinate wrote in 1751:

“We carried the map in our breast pockets across the sea, and when we arrived, we were shown swamps and rubble. But now that we were here, we began to dig – not for gold, but for truth.”

One day, Tschudi disappeared without a trace. Some reports claim he died in the Caribbean, others that he assumed a new identity in London. What remained was a web of disappointment and mistrust that burned deep into the German community.

- The recruiters – voices of promise

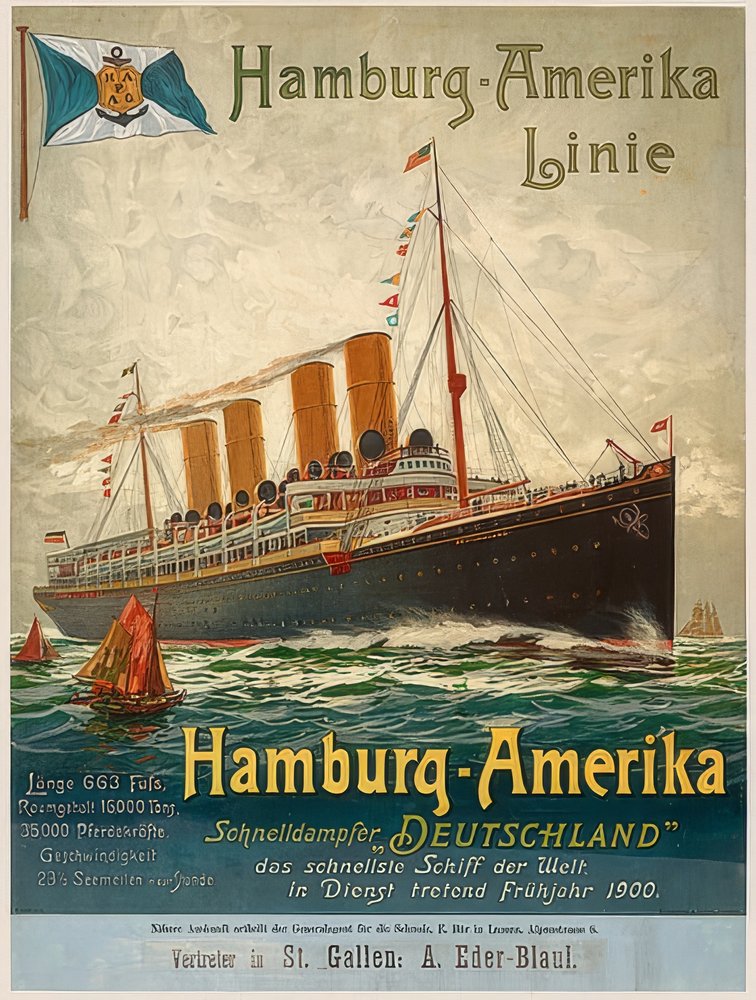

Not all lies came from individual perpetrators. From the 1720s onwards, a veritable business developed around the dream of a “new life.” Emigrant agencies opened in Rotterdam and Hamburg, advertising passage to Philadelphia. Their leaflets were titled “Report on the Blessed Land of Pennsylvania” or “Simple Description of the Wonderful New World.”

A particularly well-known pamphlet from 1726 promised:

“There, no one is another’s servant,

and the earth bears fruit without coercion.

No tithes, no war, no prince.”But what was not disclosed was that most of the ship passages were paid for on credit. Those who could not pay for the crossing in cash signed a contract of “indentured servitude” – debt bondage. Many Germans arrived in Philadelphia and had to sell their labor to rich planters or merchants for four to seven years.

Conrad Weiser noted in one of his early letters:

“They came as free people and woke up as servants.

The ships brought no hope, but mortgages.”The merchants who organized the crossing called it the “redemptioner system.”

A term that perfidiously turned the word “redemption” into its opposite.- The governor and the rebels

British Governor Robert Hunter saw the German settlers as useful subjects—hardworking, tolerant, and taxable. But when they refused to pay taxes on land that never belonged to them, he said:

“The Germans are good farmers, but bad subjects.

They believe in God, but not in laws.”Hunter sent troops to “pacify” Schoharie. But the Germans barricaded themselves in, refused to take the oath, and an open rebellion nearly broke out in the wilderness along the Mohawk River.

Johann Weiser wrote:

“We did not rise up against the king, but against deceit.

Those who promise land and then steal it sin against God, not against the crown.”- Conrad Weiser – The son between two worlds

Conrad was the mediator—between his father and the authorities, between German and English, between settlers and Iroquois. He recognized early on that property was also language. Those who spoke English owned land, while those who spoke only German remained tenants of their dreams.

In one of his notes, he wrote:

“I have learned that freedom ends in contracts

when the other person’s pen has the last word.”Conrad became a translator, mediator, and later an advisor to the colonial government.

He saw how his compatriots were cheated, disenfranchised, but also became greedy themselves. The circle began to close: the victims became property owners, and the next poor people followed.- Land deeds and the new faith

In 1740, there were more forged than genuine land deeds in circulation in Pennsylvania. German colonists bought them at markets, from wagons, and in taverns. Some knew they were fake – others did not want to know. Faith became business.

An entry in the diary of Quaker John Logan, 1741:

“The Germans are pious, but their piety is no protection against the temptation of property.”

This gave rise to a culture of justification: it was said that God had given the land – so no man could deny it. The Bible became a document, the word a title deed. A dangerous idea that ate deep into the colonies’ self-image.

- The Return of the Narrator

Philadelphia, 1887.

Ecklin is back in the archives.

He has now read not only Günter’s book, but also Weiser’s letters, Tschudi’s forged documents, pamphlets, and council minutes.

A mosaic of hopes, deceit, and faith lies before him.He notes:

“Perhaps the biggest mistake was not that they were lied to, but that they believed freedom could be bought.”

Outside, the bells of St. Michael’s German Church are ringing. On the street, a man is selling prints with the inscription: “A piece of land in Dakota – 100 acres, $10!”

Ecklin closes his eyes.

Three hundred years have passed, and the language of promise still sounds the same.“We left because we believed the land was free. Now I know: only human beings can be free – and even then, only for a short time.”